|

Crew Member

Tom Ferguson is a PhD student in the Cognition and Brain Sciences program at the University of Victoria. His research interests include decision making, statistics, data visualization, electroencephalography, acute stress, and computational modeling. Tom is interested in how we are able to integrate information about complex environments in order to guide our actions, with a particular emphasis on how we use feedback. As well, Tom wants to better understand how stress both harms and helps our ability to make decisions.

Tom was born and raised in Winnipeg, Manitoba and made his way out to the west coast for university. Tom completed both his Bachelor of Science (2014) and Master of Science (2016) degrees at the University of Victoria. Initially working with Dr. Ronald Skelton studying spatial learning and memory during his masters, Tom began working with Dr. Olav Krigolson and the Krigolson lab in 2017 and his research has now shifted more broadly to why we make the decisions we do – in particular under stressful circumstances. Tom has published articles in journals such as Cognition, Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, and Behavioural Brain Research.

0 Comments

Crew Member

Chad C. Williams is a PhD student in the Neuroscience program at the University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. He has been a member of Dr. Krigolson’s Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience Laboratory since 2015. Chad completed both his psychology undergraduate degree in 2016 and his Neuroscience Master’s of Science degree in 2018 at the University of Victoria.

Chad’s research investigates complex decision making. Specifically, he focuses on how humans would make decisions in highly demanding environments – for example, clinicians in hospitals, pilots on a Boeing 767, and now colonists on Mars. To understand decision making, he looks into the neural systems of the brain via electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Further, he integrates his findings into computational models with the goal of optimizing decision making and predicting when mistakes will occur. Alongside understanding the neural mechanisms underlying decision making, Chad has a passion for integrating the mind with technology. His first step into brain-computer interfaces was in 2018 when he established a way to control a robot with his mind. More specifically, he was able to control a Lego Mindstorm with brain waves which were measured using the Muse Headband. He is already pursuing the next step of this research; however, details are forthcoming. To date, Chad has received a total of nineteen awards (totaling $197,500) including two NSERC Scholarships (Master’s and Doctoral). He is now a second year PhD student and has published thirteen manuscripts, five of which as first author, in prominent journals including Neuroimage, Computational Brain and Behavior, and Biological Psychology. He is currently collaborating with researchers across five universities and working on projects across three countries. Crew Member

Dr. Krigolson is a neuroscientist at the University of Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada with research interests spanning decision-making, learning, statistics, game theory, electroencephalography, functional magnetic resonance imaging, and mobile neuroscience technologies. Olav completed his undergraduate degree at UVic in 1997, a MSc from Indiana University in 2003, and a PhD from UVic in 2008. Olav followed this with a NSERC Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of British Columbia until 2010 when he took up his first faculty position as an Assistant Professor in Psychology and Neuroscience at Dalhousie University.

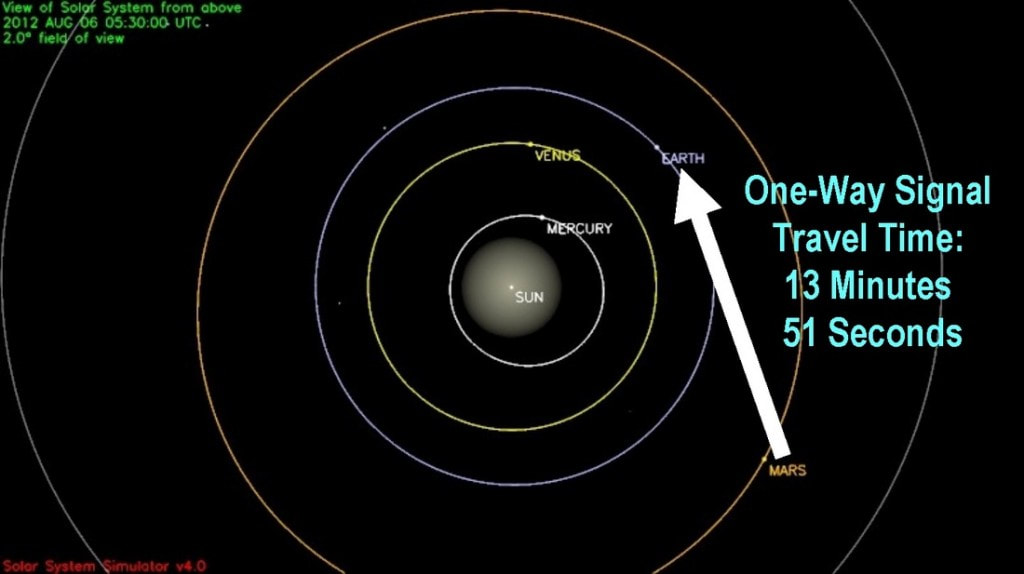

Olav’s research program has led to over 60 peer reviewed scientific publications, 200 conference presentations, and $1.6 million in grant funding for the Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience Laboratory, of which he is the Principle Investigator (www.krigolsonlab.com). His work has been published in top academic journals such as the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, NeuroImage, Psychophysiology, and Experimental Brain Research. One of his key papers, “Using Muse: Validation of a Low-Cost, Portable EEG System for ERP Research has been viewed over 29000 times (https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2017.00109/full). For his research expertise, Dr. Krigolson was awarded a prestigious Benjamin Meaker Fellowship at Bristol University in 2017: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/ias/fellowships/meakers/krigolson/). Olav’s work has gained mainstream media attention and has been featured on CBC’s Quirks and Quarks and the Rick Mercer Report. His work has been discussed on national and international TV channels, radio, and the print media including a special edition of Maclean’s magazine. Olav’s breakthroughs in the area of mobile electroencephalography (EEG, or “brain-waves”) have led to projects with NASA, major league sports, heavy industry, and local health authorities. Essentially, Dr. Krigolson was able to demonstrate that it is possible to do a full assessment of brain health and performance in under five minutes using an iPhone and a low-cost commercial EEG system available at Best Buy. The potential of this technology has led to work addressed at measuring cognitive fatigue in the workplace to improve safety, measurement and tracking of concussion, measurement and tracking of Alzheimer’s and dementia, and predicting performance within the sport and transportation sectors. Dr. Krigolson’s work led to his co-founding of Suva Technologies Inc (http://www.suva.ca/) and the company was recently featured in the Canadian Business Journal: https://www.cbj.ca/suva-technologies/. Going to Mars will not be easy... Of these factors, one of the biggest ones our research team is facing in our HISEAS mission is the communication delay. Because of the distance, the communication window varies between 4 and 24 minutes depending on the Earths position relative to Mars within their respective orbits. How this impacts us specifically is our ability to upload data and transmit it back to "Earth", in this case the Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Victoria. In reality, what this means for the astronauts is that our brain performance monitoring technology will have to be entirely contained and the data will have to be analyzed in the habitat itself.

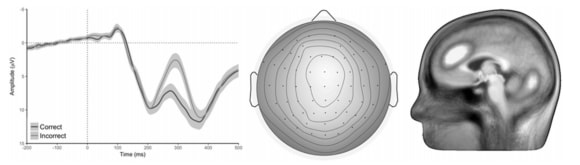

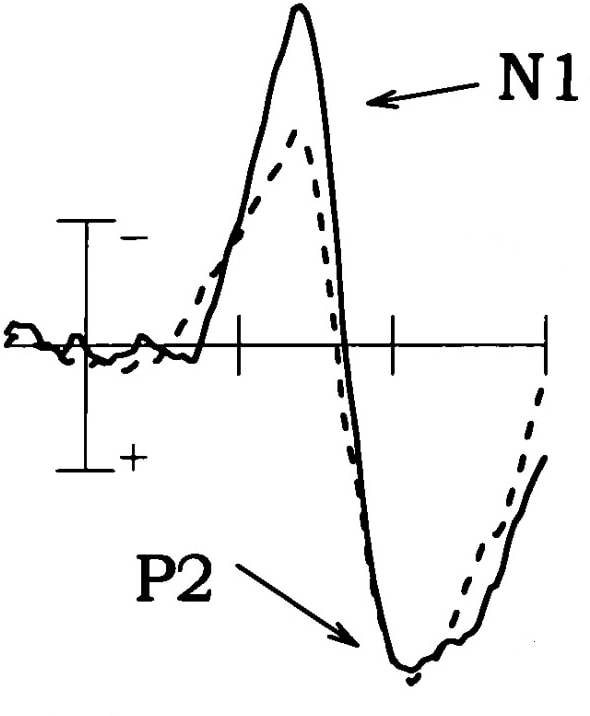

Think of it this way. Imagine an astronauts heart rate kept increasing and increasing - to the point of hitting a dangerous level and a cardiac event was imminent. Would you really want the astronaut to have to wait the maximum possible delay (48 minutes) to find out that they were in danger. This is the entire point of the technology that we are testing - the brain performance assessment can be done on site and in 5 minutes so whoever is using the technology knows immediately if they are cognitively fatigued or not. Cognitive Systems: Learning The fifth cognitive system that we will be assessing with our brain performance test is the learning system. Learning within the brain is quite complex and actually involves multiples processes and systems - the system we are focused on is our system that processes feedback (internal or external) and uses this feedback to optimize behaviour. With EEG, we can directly measure the function of this system by looking at a component of the human event-related brain potential (ERP) called the reward positivity (an ERP is an evoked response a stimulus much like the P300 mentioned earlier in this blog). As with the other aspects of cognitive function, our feedback dependent learning system is impaired with cognitive fatigue and as such we will be measuring and tracking it while we are in the HISEAS habitat.

Cognitive Systems: Decision Making The fourth aspect of cognitive function that we are measuring is decision-making. Decision-making is our ability to assess a variety of options that are in front of us and select one. Sometimes this is very easy, what some might call a System I or "gut hunch" decision and other times is a lot more challenging, what some might call a System II or "analytical" decision. In either case, like the other cognitive systems I have discussed decision-making is impacted by cognitive fatigue. However, I do not think we need a lot of research to support this idea - we have all experienced difficulty making decisions when we are tired. The problem of course in space or on Mars, is that if you make bad decisions, someone might die. The reason why we make bad decisions when we are tired is quite simple - all of the neural systems that support decision-making - memory, attention, perception are impaired. And the actual decision-making systems themselves are impaired. Given the importance of decision-making in our everyday lives this is yet another cognitive system that we will be monitoring while we are in the HISEAS habitat.

Cognitive Systems: Memory The third cognitive system that we are going to measure is memory. Again, a quick glance at a standard information processing model highlights where memory fits into neural processing. We all know what memory is - it is our ability to store and recall information. What fewer people realize is that there are at least three stages of memory. The first stage is sensory memory (not shown here). Sensory memory is literally the storage of information in neurons that are currently active (i.e., firing) and the reason it is called memory is that this storage lasts briefly after the neuron stops firing. The second stage of memory is called short term or working memory. Working memory is where we hold information that we need to currently use and may attempt to store more permanently. Right now, this definition of working memory is in your working memory! You can hold onto this information for a brief period of time - most estimates are between 30 and 120 seconds - but unless you are actively trying to maintain the "memory" it is forgotten. You may have experienced this shortly after you were just introduced to someone - their name was in working memory - you got distracted, and the name is suddenly gone. However, some of the information in working memory is pushed into long term memory where it is held for a longer duration... days to months to years. The process by which this occurs is called consolidation. Working memory is also where information that we have stored is manipulated.

In any event, memory is crucial in that we need memory to inform us so that we can make decisions. For example, when we decide what to have for lunch we access our memories to ascertain what we like and what we do not like. As noted at the outset of this post - memory is another important cognitive process and one that we will be monitoring with our brain performance assessment. As with perception and attention, memory is also impacted by cognitive fatigue and thus we will track it as one of our measures of fatigue. Cognitive Systems: Attention The second key aspect of cognitive function that I will discuss is attention, as we will be measuring that as well. While most people have been told to "pay attention", what is attention, actually? Attention is our ability to focus on something specific while tuning out other things. From a neuroscience perspective, attention translates to increasing the signal coming one area and reducing the signal from other areas (sometimes referred to as the gain of the signal). Again, the information processing model: Attention can easily be explained with an information processing model. For example, one could say that without attention sensation does not translate into perception. One can also thing along the lines that attention helps memory processing and decision-making by increasing the gain of desired inputs and diminishing the gain of other inputs. Think of why we have laws against using a cell phone while driving in terms of the above explanation. If our attention is focused on our cell phone, the gain is increased there but the gain is diminished for other sensory input - like what is happening outside of the car. Because of this, we might miss a pedestrian stepping out into the road. In terms of our brain performance analysis, attention is one of the five key components of cognitive function and as with perception, it is impacted by fatigue and thus we monitor it with EEG.

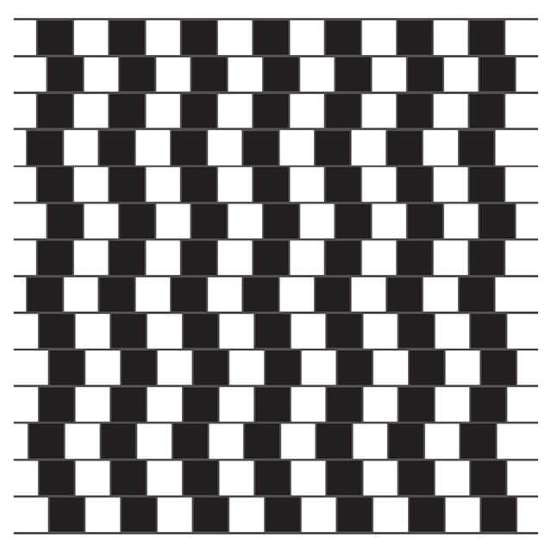

Cognitive Systems: Perception Over the next few blog posts I will be discussing the five aspects of cognitive brain function that we will be measuring via EEG, the first is Perception. What is perception? Perception is essentially your ability to interpret sensory information (sight, sound, hearing, taste, touch) into something meaningful. For example, your ability to process visual information and recognize an object as a car. Perception is an important aspect of cognitive function because without it, we would have a really hard time interacting with the world around us. One way to study perception is to examine when it is "tricked". Consider the following optical illusion below. With the above image, the horizontal lines are actually perpendicular but your perception is that they are not. This is what our perceptual system does - it interprets sensory information and tries to draw meaning from it. In this case, the meaning is wrong but you get the idea. A classic information processing model shows where perception fits into cognitive processing. We are interested in perception as the EEG signatures of sensory processing are reduced when one is cognitively fatigued. Further, given the importance of perception in cognitive processing we also examine to see the impact of other factors such as sleep, exercise, diet, etc.

|

AuthorDr. Olav Krigolson is the Associate Director for the Centre for Biomedical Research, an Associate Professor in Neuroscience, and the Principle Investigator of the Theoretical and Applied Neuroscience Laboratory at the University of Victoria. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed